Strategy

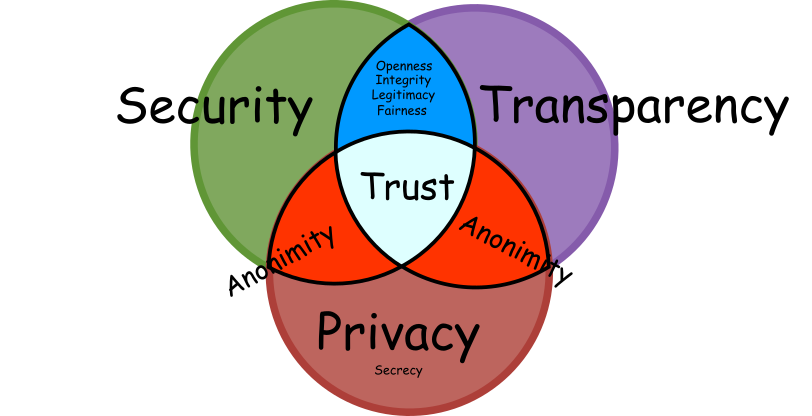

Core values for democratic voting

Accountability is a fundamental right in a well-functioning democratic society but is also a path to its demise. Protests and journalism are ways to make authorities listen to an uncomfortable opinion, and the new technology is helping with this case. Almost every citizen is armoured with a mobile phone in their pockets which can take photos and videos and spread them around in an instant to make their case heard widely.

However, the state structures of law enforcement were not asleep while the new technology came to its citizens. Instead of oppressing the protest with violence and risking their lives in uncontrollable riots, officers now have a new gun: a video camera pointed at protesters. Combined with facial recognition, the most disobedient in the protest would be prosecuted one by one after the protest would be long gone, imprinting paranoia and fear in those who may express their opinion.

For effective democracy, we would want that the power lacks such granular tools for accountability of its citizens, which is what the human right to privacy is about. Unfortunately, the age of effective protests seems to have passed as authorities have gained more and more tools for surveillance and behaviour manipulation. Thus, the ballot box is the next best place where we can express our opinions freely.

The ballot box, in essence, achieves two things. The first is that it forms a global consent that every voice is heard equally. And the second one is that neither your bank, employer, or friends would not be able to coerce you and hold you accountable for how you have voted by preserving the everlasting anonymity of your vote.

It is very easy to spoil these two properties in the name of security. A simple change where election officials are sourced like a pool of army soldiers ends democracy even if soldiers faithfully follow trustworthy protocol for pooling station operations. How would an ordinary citizen tell whether army soldiers were following election protocol honestly and not following an order from a dictator?

“It’s not the people who vote that count, it’s the people who count the votes.” A meme on Joseph Stalin

Perfect security is worthless for trustworthiness without transparency. In democratic elections which use paper ballots, transparency is often ensured by sourcing election officials from local communities where a pooling station is located and being open for anyone to observe the faithful execution of election protocol at the pooling station. Even more, every pooling station publishes its result independently; thus, two neighbouring pooling stations would keep themselves cross-accountable as we would expect their results not to deviate too much from each other. For example, this is one of the ways we know that the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus were rigged.

It is exciting to look into how a lack of security or too much transparency could violate the anonymity aspect of privacy. In the early days of the secret ballot, multiple ways of vote selling strategies were devised to keep voters accountable to their bribers in a blend with the help of insiders, violations of protocol or exploiting its weaknesses. For example, we would find it unacceptable to have a camera in the voting booth (unless you are part of the population who like to take selfies with their ballots that you sholdn't). So there must be good security in place, which we shall define as:

Security: procedures which enforce desired behaviour of agents and machines

This definition purposefully takes out the entity whom it protects. For instance, in computerised elections, the desired behaviour can be enforced with software independence which produces evidence that no malware on the computer could have manipulated the result. The catch, though, is who can access the proof of it to be audited, and this is where transparency comes into play which we shall define:

Transparency: evidence and openness which ensures trustworthiness that the correct goal gets achieved

For instance, an election system which provides conclusive public evidence of all necessary properties of fair and democratic election results but lies on an assumption of good-intentioned agents to produce the result successfully wouldn’t be considered as secure. Transparency also is in tension with privacy in a different way than security. In particular, we wouldn’t find it acceptable if the link between votes and voters were published and used as evidence for trustworthy elections. Instead, the evidence must be such that it conclusively proves that only voters from a particular pool have cast only one vote producing the election result, which is crucial evidence for democratic remote electronic voting.

Note that in literature, security, transparency, privacy and accountability values are often defined differently. Security is often treated as freedom from danger, here though a positive goal-oriented notion is used. Similarly, privacy sometimes is defined instrumentally in what it allows or enables to do, whereas here I define it as a capacity to act autonomously, like not being accountable to anyone of your choice in elections. We could define transparency as verifiability plus openness for participation in verification which could be understood in either bureaucratic, technocratic or in democratic frames.

- Ronald L Rivest, On the notion of ‘software independence’ in voting systems, 2008.

- Sunoo Park, Michael Specter, Neha Narula, Ronald L Rivest, Going from bad to worse: from Internet voting to blockchain voting, 2021.

- Olivier Belanger, Randi Markussen, Lorena Ronquillo, Carsten Schurmann, Framing Electoral Transparency: A Comparative Analysis of Three E-vote Counting Ceremonies, 2016.

- Josh Benaloh, Ronald Rivest, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Philip Stark, Vanessa Teague, Poorvi Vora, End-to-end verifiability, 2015.

- Ibo van de Poel, Core Values and Value Conflicts in Cybersecurity: Beyond Privacy Versus Security, 2020.

- Ralf Küsters, Tomasz Truderung, Andreas Vogt, Accountability: definition and relationship to verifiability, 2010.

- Wojciech Jamroga, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Steve Schneider, Carsten Schürmann, Philip B. Stark, A Declaration of Software Independence, 2021.

- Carissa Véliz, Why Democracy Needs Privacy, 2021.

E-voting

Perhaps before we dive into the technical challenges, we need to get in touch with reasons why e-voting could be a good idea and is a problem worth investing time and resources in. Often the top benefits of voting are laid out as being more accessible, less intrusive in our daily lives and making elections and referendums cheaper so they could be run more often. The cheapness, however, has not yet materialised and is on the trajectory to never be to which we will get in a second.

What is, however, often overlooked and merely stated to be more efficient is that with remote electronic voting, it is possible to have more complex ballots (this is, however, rarely emphasised due to the limitations of many existing systems)! Computers are efficient, and there is no added computation cost on whether it counts votes for a preferential voting system or a complex ballot. It is fairly easy to imagine a ballot which enables voters to vote on what municipality projects need to be realised given a budget constraint.

It may also be possible to construct a multiple-question ballot where each voter has an opportunity to cast multiple votes for the propositions which he/she feels strongly about, bringing in space for different minorities to work together in harmony without feeling to be overpowered by majorities.

There is also an opportunity to sample voters randomly for less important decisions so that voters would not be overwhelmed with decision-making. Or alternatively, the propositions could be sampled randomly for each voter so that each voter would have to spend less time on decision-making. In contrast, a collectively large number of decisions would have been decided democratically.

Also, another direction where voting could be eye-opening is that it is possible for vote counting to happen fluidly during the serving term of representatives. For instance, when the trust for an elected candidate has been lost, the voters could change their choices in the midterm, making the official lose his seat, which would be a great addition to keeping representatives accountable.

Unfortunately, all these benefits have been put on the sidelines for voting systems. In fact, most popular designs make it even harder to have preferential voting when homomorphic vote counting is used as a cryptographic primitive. But why just not take venture capital and build an app which would do all these things? The answer is remarkably ironical, and it's because of efficiency.

To help you see that, imagine if it would be possible to have a single ballot box for a whole nation. Since it would be so efficient, it would suffice to be managed by a few officers. When you vote, you would see all the same procedures and gatekeepers in place as in a less efficient variant. The main problem is: how could you be sure that the efficient officers are not deviating from a protocol? Neither would you see cross-accountability between neighbouring pooling stations nor know any of the officers who count the votes. And you know the famous phrase by Stalin, don't you?

To make it clear, privacy is hard because a large amount of data can be copied instantly or silently collected during casting. At the same time, accountability is hard as a large amount of data can be manipulated at scale without leaving any traces. Thus we put a final nail on the idea that we could leave elections to our efficient voting officers and pay them handsomely, to be honest.

To increase the trust that the adversary would not be able to see how the voter casts his vote, a mixnet cascade is often used. With it, as long as one party managing the mix honestly acts, there is no way for an adversary to determine how the voter has voted, even if he had control over all other parts of the system.

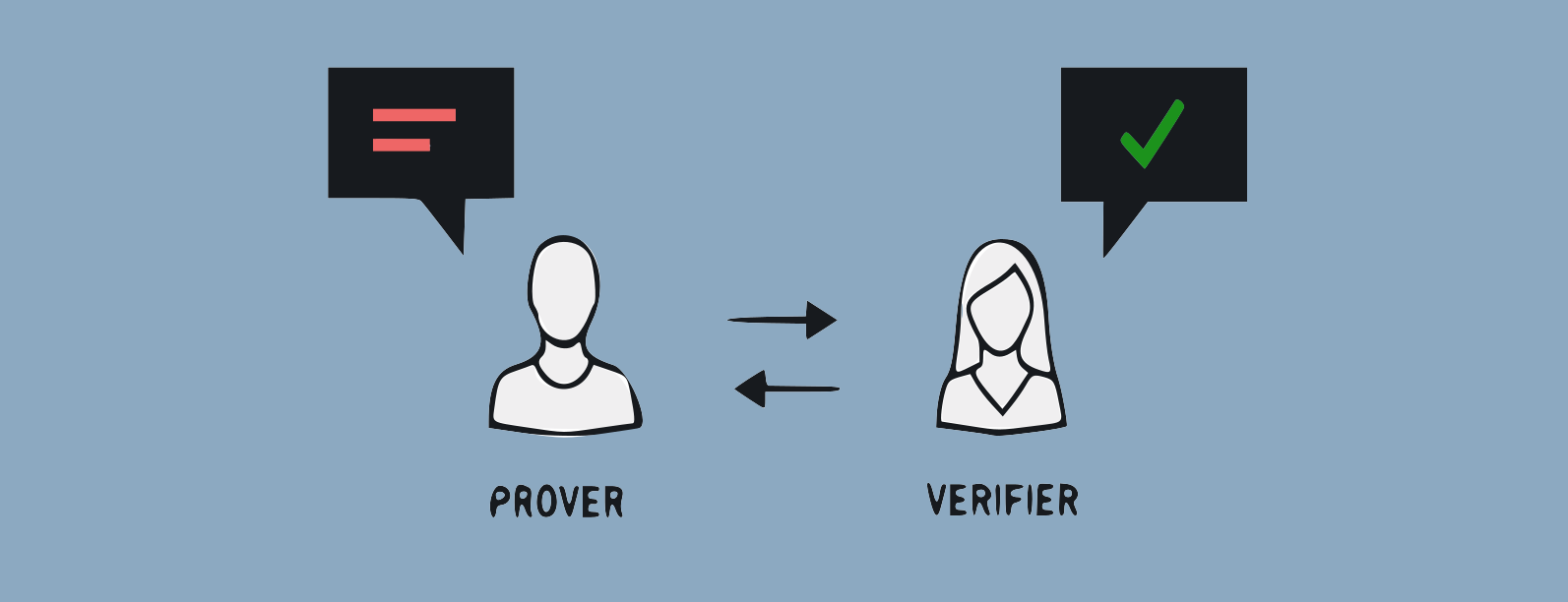

The second issue we need to track is accountability that neither involved party had not manipulated the election result. There are multiple ways to do it, but using re-encryption mixnets together with zero-knowledge proofs of shuffle does not compromise privacy when revealing the evidence to the public. So is voting already solved the problem?

Not quite so. Due to the use of encryption mixnet, the ballots are limited to casting only multiple option questions. The accountability often comes only after the elections have been run. Thus if the adversary spoils one of the keys to the mixed election results, the election result would not be possible to decrypt. The centralisation of the system makes it prone to DDOS attacks, and what if an adversary spoils the vote casting experience for demographies that do not cast favourable votes and perform a negative vote-buying strategy?

- Alexander Schneider, Christian Meter, Philipp Hagemeister, Survey on Remote Electronic Voting, 2017.

- Matthew Bernhard, Josh Benaloh, J. Alex Halderman, Ronald L. Rivest, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Philip B. Stark, Vanessa Teague, Poorvi L. Vora, Dan S. Wallach, Public Evidence from Secret Ballots, 2017.

- John Morgan, Negative Vote Buying and the Secret Ballot, 2010.

- Krishna Sampigethaya, Radha Poovendran, A framework and taxonomy for comparison of electronic voting schemes, 2006.

- J Paul Gibson, Robert Krimmer, Vanessa Teague, Julia Pomares, A review of E-voting: the past , present and future, 2016.

- K. Sampigethaya, R. Poovendran, A Survey on Mix Networks and Their Secure Applications, 2006.

Alternative

All these remaining issues have a common root: remote electronic voting is modelled as a pooling station. Technically such voting systems anonymise votes before they are decrypted. An alternative approach mentioned on the sidelines of a few papers is to anonymise voters before they cast their votes. That sounds complex, but stay with me for a moment!

Consider you are in an alternative universe where secret paper ballots were not invented. Instead, they had a ballot based on the ropes with a bit of electricity. Here is how it works. Upon entering a pooling station, each voter gets distributed a rope containing a wire for communicating his choice, just like an old telegraph. Before voters can cast a vote, they come together and form a knot tying together all ropes. Then the ends of the votes are attached to a display where each voter, in secrecy at the other end, sends a signal corresponding to the vote simultaneously with other voters.

Although highly impractical, it fulfils the requirements for the voting system to ensure security, transparency and privacy. In such ballots, we can easily ensure that no votes have been discarded, added or manipulated by just seeing that number of incoming ropes held by voters are equal to the number of ropes at the monitors and that no rope has been cut and added along the way. Whereas privacy is maintained, presuming that no one could follow through an incoming rope to the outgoing one at the knot.

Important to note is that in this example, the rope represents a pseudo-identity, and the anonymisation happens for the voters rather than the votes. However, the result that no vote can be linked to a corresponding voter is the same. In addition, there are no limitations on how complex the ballot is as it can be easily transferred over the wire. The problem, though, is: how can we tie such a robust knot with computers?

The first step is to separate a braiding phase where the knot is being tied from the vote-casting phase. This enables the voter to cast a vote in secret by signing it with his secret key and delivering it anonymously to the closest vote collection place, which can verify if the signature comes from a valid pseudonym produced after braiding.

With such separation, the centralisation issue disappears as anyone can participate in collecting casted votes preventing the adversary from stopping the election from happening or doing negative vote buying. In addition, accountability comes before elections are run; thus, in case of security issues have been detected, they can be fixed before the votes are cast, improving the trustworthiness of the election result when it arrives. It is also possible to add decent antibribery and anti-coercion resistance by giving each voter a choice to revote in secret in a pooling station with a paper ballot. (Remote extension is also possible by randomly preallocating secret vote collection stations to voters and still keeping transparency by cross accountability between stations and a reasonable expectation that only a minority of voters would have cast in secret vote collection stations and thus would affect election result marginally. )

The accountability of the election also simplifies. We only need to check that each outgoing pseudonym from the knot is owned by one incoming pseudonym and that only votes with valid pseudonyms are collected and counted. Fortunately, there are ways to do that.

How to tie a strong knot

Imagine a classroom full of people where the teacher passes through a blank page on which each pupil shall write his secret pseudonym signature and folds it in before passing the page to the next pupil. After the page had gone through the class, the teacher opens the page and gets the list of all pseudonyms.

The page is passed through a second time to assure their legitimacy and that the teacher had not made it up to boost their own popularity. This time each pupil is asked to sign the page if he/she can find their pseudonym signature in the list. When all signatures are collected, the end result is a knot with input and output pseudonyms where exactly each pupil owns one pseudonym, but you would not be able to tell whom. Thus it is an exact equivalent of the knot.

Such setups have actually been implemented in the blockchain context, as in the CoinShuffle protocol. The beauty of this approach is that one needs only a cryptographic signature scheme to make it work. In addition, only partial synchronicity is necessary between members as multiple braiding steps can be performed between different pseudonyms staging multiple knots. Thus if eventually a quantum computer is being built, we can just replace cryptographic primitives with QC-resistant counterparts.

An alternative that held a great promise decades ago is using blind signatures. In this setup, you would put your pseudonym in the envelope and come in at the voter's registration place, where the authority would put a stamp on an uncovered place without revealing the vote. Then each voter could use the stamped pseudonym as proof that his secret pseudonym is eligible to participate in the elections.

One major drawback in such setup is that there is no way to be assured that the adversary could have gained access had put a stamp on his own pseudonyms. For this reason, blind signatures have been sidelined in voting system designs. Nevertheless, it is a cool primitive which enables an authority to enforce quotas without violating users' privacy.

Another promising primitive is using a ring signature scheme. Such a primitive enables every member of the group to issue a signature on behalf of the group, and with additional primitives, it can be possible to tell if two signatures belong to the same member. However, one of the main obstacles to using it in practice for voting systems is that signatures computation costs and its length grows substantially with group size (like one initially used in Monero). Alternatively, more efficient schemes exist, but they do introduce an initial setup phase to generate a common reference string which, if compromised, can enable an adversary to issue a valid signature (like one used in ZCash). So it seems that we do need to resort to a teacher in the classroom moving a page around to tie strong uncompromisable knots.

Fortunately, there is an alternative employing zero-knowledge proofs of shuffle. Although proofs of shuffle have mainly been used in re-encryption mixnet where mixes are set as a pipeline for the votes, it can also be used for forming anonymised pseudonym sets. As it is an integral part of the PeaceFounder's voting system design, let's have a closer look at how it does work for a set of voters:

(Setup) Each voter generates a secret key

yand publishes a public keyY <- g^yto a roster approved by election organisers. After every participant has done so, we have a list of eligible public keys:

<Y_1, Y_2, Y_3> with a relative generator gA mix then re-encrypts and shuffles all member pseudonyms as public keys taking

gand a relative generatorX <- g^x, wherexis its session-generated secret key:

(a, b) <- (X^r, Y * g^r)

<(a_2, b_2), (a_3, b_3), (a_1, b_1)>Procedingly mix uses his secret key and calculates the new public key with a relative basis. In the end, forming an eligible public key list on a new basis:

Y' <- b^x/a = (Y * g^r)^x / X^r = Y^x

<Y_2', Y_3', Y_1'> with a relative generator XFinally, each voter can then issue ordinary signatures with relative generator

X, which would have a public keyY' <- X^y. The signature would be recognised as belonging to one group member but anonymous because of shuffling. The procedure can be repeated multiple times with different mixes, thus solidifying anonymity.

The mix does not calculate the shifted list <Y_2', Y_3', Y_1'> directly as Y^x because there is an efficient and robust zero-knowledge proof available for step 2 and step 3. In particular, proof of shuffle (step 2) has multiple propositions on how to do them efficiently, but one particularly stands out: the WikstromTerelius variant implemented the Verificatum project. It is capable of encrypting 100k ciphertexts in under 30 min, scales linearly, have been deployed in real elections around Europe and is being used in national elections in Estonia. In addition, it is available under an MIT licence and is patent-free. Even more, the setup to use the WikstromTerelius ZK PoS phase is trapdoor free as common reference strings can be generated verifiably random — a rare occurrence in the vast literature of zero-knowledge proofs. Similarly, for step 3, a zero-knowledge proof of decryption can be used for which a well-known and straightforward trapdoor-free implementation exists.

The end result is that the mixing part can be safely delegated to a third party whose security is not of any concern as long as it can make correct proofs with a given specification. It would not be far-fetched that an ordinary citizen with a small desktop computer could take part in anonymising pseudonyms for local elections without either party worrying that they messed things up. Because of this property, this voting system exhibits strong software independence, where mistakes can be fixed without needing to rerun elections. Thus although the voting system runs one of the most complex computations during anonymisation, it is cheapest to run and deploy as security comes free.

Essential resources for zero-knowledge proofs:

- David Chaum, Torben Pryds Pedersen, Wallet Databases with Observers, 1993.

- Vitalik Buterin, Some ways to use ZK-SNARKs for privacy, 2022.

Recomputing public keys for shifted generators and their variations have already been proposed together with voting systems but seem to have been sidelined:

- Peter Y. A. Ryan, Crypto Santa, 2016.

- Rolf Haenni, Oliver Spycher, Secure Internet Voting on Limited Devices with Anonymized DSA Public Keys, 2011.

- Andrew Neff, A Verifiable Secret Shuffle and its Application to E-Voting, 2001.

For WikstromTeralius variant of shuffle, check out:

- Douglas Wikström, A Sender Verifiable Mix-Net and a New Proof of a Shuffle, 2005.

- Douglas Wikström, A Commitment-Consistent Proof of a Shuffle, 2009.

- Björn Terelius, Douglas Wikström, Proofs of Restricted Shuffles, 2010.

- Rolf Haenni, Philipp Locher, Reto Koenig, Eric Dubuis, Pseudo-Code Algorithms for Verifiable Re-encryption Mix-Nets, 2017.

- Douglas Wikstrom, How To Implement A Stand-alone Verifier for the Verificatum Mix-Net, 2011.