Challenge

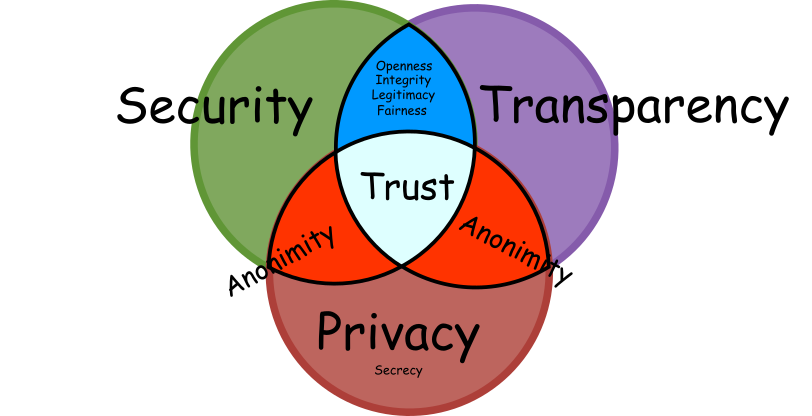

The core foundation of any trustworthy democratic voting system rests on three pillars: Security, Privacy, and Transparency. Their harmonious interplay ensures that each vote not only counts but is also protected and verifiable.

At the heart of the process, the ballot box symbolises democratic ideals. It represents the universal acceptance that every voice matters equally and the conviction that no external entity, either your bank, employer, or friends, should infringe on your voting choice. This sacredness of choice is enshrined in the age-old principle of vote privacy.

Security ensures that your vote remains uncompromised. We can define it as procedures which enforce the desired behaviour of agents and machines. Security is the backbone of the voting process. In the modern age, with computerised elections, the essence of security lies in software independence. This ensures no malware or rogue program skews the results. Yet, the integrity of this system rests on who can access and audit its outcomes.

Transparency, the second pillar, shines a light on the process, making it observable and accountable. It is the evidence and openness which ensures that the correct goal gets achieved. In traditional paper-ballot elections, transparency is manifested when election officials, sourced from local communities, manage polling stations openly. By declaring its results independently, each station engages in a system of mutual accountability with its peers. Discrepancies, as witnessed in events like the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus, highlight the importance of transparent checks and balances.

Yet, the drive for complete transparency can sometimes conflict with the need for privacy. In our quest for public verifiability, we must be wary of oversharing, such as revealing the direct link between votes and voters. The challenge lies in providing conclusive evidence of a vote's origin without compromising a voter's identity, especially in scenarios like remote electronic voting.

The final pillar, Privacy, revolves around the sacredness of one's vote. While security and transparency have their challenges, ensuring the absolute anonymity of a vote has its own set of hurdles. The voting history is full of strategies that tried to undermine privacy, from vote-selling plots aided by insiders to procedural violations. An evident breach of this principle would be the presence of a camera in a voting booth. While some may view this as a security measure or a chance for a ballot selfie, it fundamentally undermines the essence of vote privacy.

Paper ballots have been the traditional method of voting in many democracies and offer specific benefits in terms of security, transparency, and privacy. Here's how these three requirements are satisfied:

Security:

Tamper-evidence: Once votes are cast and placed inside sealed ballot boxes, any unauthorized access or tampering becomes evident when the seals are broken or boxes are physically damaged.

Physical safeguards: Ballot boxes are typically guarded and stored in secure locations, preventing unauthorized access.

Simplicity: The simple nature of paper voting, where voters mark their choice and deposit it into a box, minimizes the potential for complex attack vectors.

Transparency:

Public counting process: Counting of paper ballots is typically done in a public or observable manner, allowing representatives from different political parties, independent observers, and sometimes even ordinary citizens to witness the process, ensuring fairness.

Physical trace: Each paper ballot serves as a tangible record of a voter's intent, which can be reviewed, recounted, or audited if necessary.

Privacy:

Anonymity: Once a paper ballot is deposited into a ballot box, it becomes anonymous. There's typically no way to link a ballot back to the voter who cast it, ensuring voter privacy.

No trace: Paper ballots don't leave traces or logs that can be analyzed later to determine voting patterns or voter identities.

Isolated act of voting: Voting booths or enclosures ensure that the act of marking a ballot is private, preventing others from seeing a voter's choices.

The fundamental property for a paper ballot that guarantees security, transparency and privacy is inefficiency, which results in the distribution of responsibilities and management of multiple pooling stations. To help you see that, imagine it would be possible to have a single ballot box for a whole nation managed by a few officers. When casting a vote, you would see all the same procedures as usual. However, as fewer officers are needed, the opportunities for adversaries to infiltrate the system would become much more lucrative. Bribing a few officers to add more votes to the tally or a desirable candidate or installing a secret camera at the voting booth to see how every voter has voted is more accessible when the system is centralised.

Computers make the process much more vulnerable as there is no way to observe the operation of the computer. As the ballots are no longer physical, there is nothing to observe or recount. The efficiency of it obscures observation for it's correct operation. It can freely copy a large amount of data in an instant, collect that during casting, or manipulate large amounts of data at scale without leaving any traces. The computer consists of many chips inside it, each of which could host a malicious program. It gives the adversary opportunities as finding what is modified is as impossible as finding a needle in a haystack. Thus, how could we trust our vote to the computers?

These are challenges which are addressed by E2E verifiable voting systems. Privacy can be addressed using a mixnet cascade, which allows severing the link between the voter and the vote. But this enlarges the surface area for adversaries to infiltrate the system and manipulate the final tally. To address that, the most common solution is to use ElGamal re-encryption, where efficient zero-knowledge proofs to assert the honesty of the mixes exist.

However, to keep the link between voters and votes scrambled between multiple parties, a threshold decryption ceremony must be used. The fundamental idea behind threshold decryption is that no single entity should possess the complete decryption key. Instead, the key is split among several parties, and only when a predefined number of these parties come together can they decrypt the votes. This process addresses security, transparency, and privacy in several ways:

Security:

Protection against single points of failure: By distributing the decryption key among multiple parties, the system protects against a compromised or malicious party. An attacker would need to compromise a majority of the parties to decrypt the votes, which significantly raises the bar for any hacking attempts.

Defends against insider threats: Even if one or more entities involved become compromised or act maliciously, the system remains secure as long as the threshold is not reached.

Mitigates key exposure risks: The risks associated with the loss, theft, or exposure of the decryption key are mitigated since the key is scrambled between multiple parties.

Transparency:

Multi-party verification: Multiple parties in the decryption process provide a built-in oversight. Each party can verify the actions of others, ensuring that the process is carried out correctly.

Auditable process: The ceremony produces cryptographic proofs at each step, allowing third-party auditors or observers to verify that the decryption was performed correctly without compromising voters' privacy.

Public confidence: Knowing that multiple potentially adversarial parties must cooperate to decrypt votes can bolster public trust in the election's integrity.

Privacy:

Anonimity: With the decryption key split among different parties, the risk of unauthorised vote decryption is reduced. Even if a party wanted to violate voter privacy, they couldn't do so without the cooperation of the other key holders.

A significant burden to this primitive is the complex nature of multi-party ceremonies. This requires a meticulous risk assessment, as an error in gauging the trust threshold could lead to undecrypted election results. Also, coordination of protocol execution and troubleshooting is not a simple task when adversaries sabotage communication channels. Alternatively, a conservative approach might endanger voter's privacy, especially if an adversary manages to assemble the complete key in the future. The result's declaration is also not immediate. The announcement is contingent upon the completion of the threshold decryption protocol, a process that becomes progressively time-consuming as the number of participants and voters increases.

Further complicating matters is the inherent limitation concerning ballot types. Due to constraints in encoding bits within the generator exponent, certain ballots, such as cardinal or budget-planning ones, are challenging to support. This, combined with multiparty protocol coordination, often discourages smaller organisations from adopting these systems. Instead, they lean towards solutions that might sacrifice transparency for simplicity. Such choices invariably raise doubts about the integrity of the final tally.

In the realm of pre-deployed voting solutions, while they can offer assurances regarding election integrity, the same can't be said for voter's privacy. The intrinsic complexities of threshold ceremony protocols stifle the emergence of a vibrant market for independent decryption providers. There's a growing concern that the anonymisation process in predeployed systems is more of a lipstick service, especially when a single entity controls the anonymising mixes.

Overall, the complexities of deploying a threshold decryption ceremony are significant compared to a paper ballot system for the same security, transparency and privacy guarantees. This is where PeaceFounder offers a more adequate solution.

Note that security, transparency, privacy and accountability values are often defined differently in literature. Security is often treated as freedom from danger, though a positive goal-oriented notion is used. Similarly, privacy is sometimes defined instrumentally in what it allows or enables to do. In contrast, I define it as a capacity to act autonomously, like not being accountable to anyone of your choice in elections. We could define transparency as verifiability plus openness for participation in verification, which could be understood in either bureaucratic, technocratic or democratic frames.

- Ronald L Rivest, On the notion of ‘software independence’ in voting systems, 2008.

- Sunoo Park, Michael Specter, Neha Narula, Ronald L Rivest, Going from bad to worse: from Internet voting to blockchain voting, 2021.

- Olivier Belanger, Randi Markussen, Lorena Ronquillo, Carsten Schurmann, Framing Electoral Transparency: A Comparative Analysis of Three E-vote Counting Ceremonies, 2016.

- Josh Benaloh, Ronald Rivest, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Philip Stark, Vanessa Teague, Poorvi Vora, End-to-end verifiability, 2015.

- Ibo van de Poel, Core Values and Value Conflicts in Cybersecurity: Beyond Privacy Versus Security, 2020.

- Ralf Küsters, Tomasz Truderung, Andreas Vogt, Accountability: definition and relationship to verifiability, 2010.

- Wojciech Jamroga, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Steve Schneider, Carsten Schürmann, Philip B. Stark, A Declaration of Software Independence, 2021.

- Carissa Véliz, Why Democracy Needs Privacy, 2021.

- Alexander Schneider, Christian Meter, Philipp Hagemeister, Survey on Remote Electronic Voting, 2017.

- Matthew Bernhard, Josh Benaloh, J. Alex Halderman, Ronald L. Rivest, Peter Y. A. Ryan, Philip B. Stark, Vanessa Teague, Poorvi L. Vora, Dan S. Wallach, Public Evidence from Secret Ballots, 2017.

- John Morgan, Negative Vote Buying and the Secret Ballot, 2010.

- Krishna Sampigethaya, Radha Poovendran, A framework and taxonomy for comparison of electronic voting schemes, 2006.

- J Paul Gibson, Robert Krimmer, Vanessa Teague, Julia Pomares, A review of E-voting: the past , present and future, 2016.

- K. Sampigethaya, R. Poovendran, A Survey on Mix Networks and Their Secure Applications, 2006.