The shift from prevention to detection and accountability

AI

Traditional paper ballots rely on prevention—poll workers and observers are physically present during voting to ensure manipulation doesn't occur in the first place. With e-voting, we lack this luxury. Malware affecting the election result can hide in any of the hundreds of chips or within gigabytes of operating system code that make up a modern computer, making spotting malware in action as easy as finding a needle in a haystack.

Verifiable remote voting transforms the security model from prevention to detection. Rather than preventing manipulation during voting, the goal is to detect any manipulation of the tally afterwards, providing cryptographic evidence that anyone can verify at any time. This evidence must prove the tally contains only votes from registered voters who cast at most one vote (universal verifiability) and enable voters to verify their vote was counted (individual verifiability), all while preserving vote privacy.

This transforms election oversight. Instead of observers preventing fraud alongside administrators in real-time, anyone can independently verify cryptographic proofs after the voting phase closes. The registrar maintains the list of eligible voters—the same trust assumption as paper ballots, and even this can be verified through sampling. Disputes can be resolved through independent cross-border audits, eliminating the need for coordinated real-time oversight. This enables administrators to focus on operational security and redundancy, where only one honest machine among many is needed for resiliency from sabotage.

PeaceFounder addresses the verifiable remote voting challenge through three mechanisms, each solving a fundamental problem in making electronic voting both verifiable and private. These mechanisms build on well-established cryptographic primitives—exponentiation mixes (Haenni & Spycher 2011, Ryan 2016, Selene 2016), Pedersen commitments, verifiable shuffles (Wikström 2005, Verificatum 2011), and history trees (Crosby 2009).

CC: Jānis Erdmanis

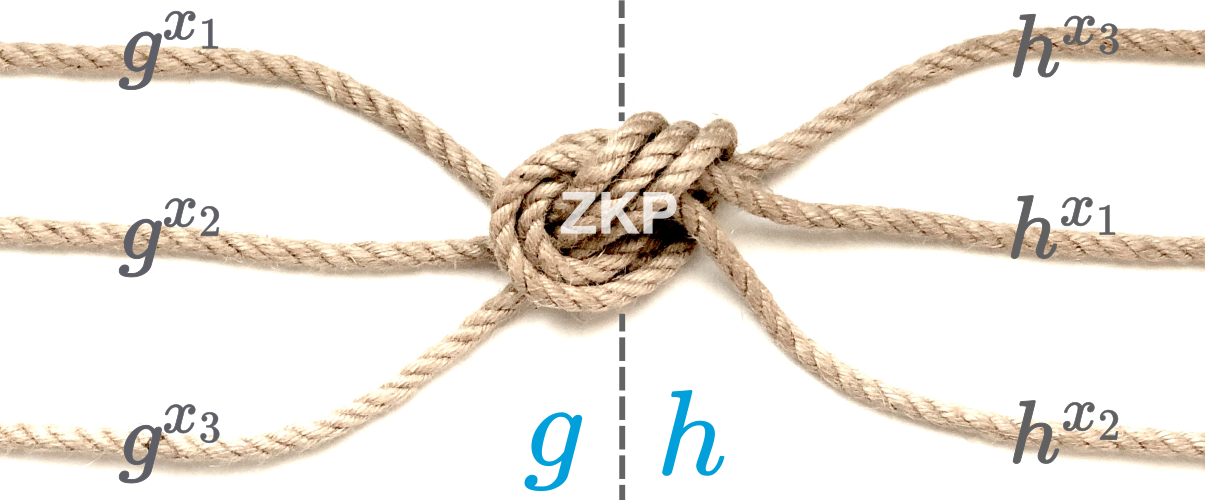

Instead of anonymising votes to sever the link between voter and vote, we anonymise the voters' pseudonyms themselves, with which voters sign their votes, proving they are eligible. Think of this as creating a cryptographic knot with colored threads. Your identity enters as a red thread, and your voting pseudonym exits as a blue thread. Multiple independent parties take turns braiding these threads together—each adding their own knot one after another.

Cryptographically, this braiding works through an exponentiation mix. Each voter starts with a generator gi and a public key Yi,j in position j. A braider applies a secret exponent x and permutation χ while the zero-knowledge proof assures integrity linking input pseudonyms {Yi,j}j with output pseudonyms {Yi+1,j}j:

πBraid=PoK{(χ,x):gi+1=gix∧Yi+1,j=Yi,χ(j)x} This zero-knowledge proof demonstrates that the braider performed the transformation correctly without revealing their secret exponent or permutation. Anyone can verify that the knot preserves the count and that each twist was performed correctly, yet following any individual thread through the knot becomes computationally impossible under the discrete logarithm hardness assumption. Even if most braiders collude, as long as one remains honest, your anonymity holds.

The advantage of braiding is that it requires no coordination ceremonies—parties can braid one transaction at a time, completely independently, greatly expanding the number of independent parties who strengthen your anonymity. This creates your anonymous voting identity: a pseudonym that's cryptographically unlinkable to your real identity, yet provably belongs to an eligible voter. When you vote, you'll sign your ballot with this pseudonym, ensuring it counts while keeping you anonymous.

CC: Jānis Erdmanis

The voting system introduces a novel security mechanism for individual verifiability grounded in observable isolation from communication.

Picture yourself as a detective interrogating a suspect about a crime. Before questioning begins, you place your suspect—in this case, your voting calculator—into custody, completely cut off from the outside world. No phone calls, no messages, no communication whatsoever. Meanwhile, new evidence emerges: the crime scene investigation completes, witnesses are interviewed, forensics come back. Your suspect, isolated in custody, cannot possibly know what this new evidence reveals.

When you finally interrogate your suspect with this fresh evidence, their response tells you everything. If they're honest, they'll describe details that match the crime scene perfectly—because they were actually there. If they're corrupt and trying to deceive you, they can only guess randomly—and their guesses won't align with reality.

Now let's see how this interrogation unfolds in practice. During voting, your calculator generates secret tracker preimage values θ,λ∈Zq along with your vote choice v∈Zq. These are committed using a homomorphic commitment scheme (Pedersen commitments):

V=Com(v),Q=Com(θ),R=Com(λ) publicly signed with a pseudonym, openings with blinding factors are sent over an encrypted channel to the tallier. After you cast your vote, isolate your voting calculator by disconnecting it from all networks—put it in airplane mode, use a Faraday cage, or turn it off. This isolation must occur before challenges are announced, ensuring the calculator cannot learn what trackers appear on the tally board.

⚠️ Vote tagging by a malicious calculator: A malicious calculator can embed identifying information into an encrypted ballot by controlling cryptographic randomness (e.g., encrypted channel parameters or signature nonces), thereby breaking the anonymity of the submission channel. This can be mitigated by forcing the incorporation of entropy from the voter's device at the protocol level. We omit this detail here for clarity; it is explained in the full paper.

Once the voting phase closes, the tallier derives a verifiably random seed from all submitted tracker preimage commitments:

seed=Hash({Qi,Ri}i) This seed generates unique challenges for each voter through a pseudorandom generator:

{ei}i←PRG(seed) You receive your unique challenge ei and type it into your isolated calculator. The calculator computes your tracker using the formula:

t=eθ+e2λ(modq) where e2 represents the square of the challenge. This dual-component design, with the quadratic term and one-attempt limitation (made user-error-free via a checksum), prevents extrapolation attacks—computations with arbitrary challenges during voting could enable a coercer to derive the real tracker once the voters' unique challenges are announced. The voter then uses this tracker to locate their vote on a public tally board {ti,vi}i.

Why not t=eθ+λ ?

A malicious calculator could set θ=0 to predetermine t=λ, knowing this tracker will appear on the tally board. This enables a many-to-one attack: multiple voters get the same tracker while the calculator manipulates votes undetected. The quadratic formula prevents this by ensuring no non-trivial null space in the challenge-independent direction.

We don't simply trust the tallier to correctly associate trackers with votes. Without cryptographic binding, a corrupt tallier could assign the same tracker to multiple voters while manipulating the freed votes. To eliminate manipulation, we support the tally board with a zero-knowledge proof, ensuring the tally's integrity under the discrete logarithm hardness assumption.

The first step is for the tallier to compute tracker commitments publicly using the homomorphic properties of the commitment scheme:

Ti=QieiRiei2=Com(ti) Then it jointly shuffles tracker commitments with vote commitments, which has a well-understood zero-knowledge proof of shuffle:

πPoS=PoK{ψ:Ti=Com(tψ(i))∧Vi=Com(vψ(i))} where permutation ψ and blinding factors for the commitments remain secret. This proof assures us that the published tally board {ti,vi}i corresponds to the tally board commitments {Ti,Vi}i in shuffled form.

Incidentally, the use of Pedersen commitments provides perfect information-theoretic hiding—even a computationally unbounded adversary cannot determine the committed values from the commitments alone. This provides everlasting privacy in the public evidence: your vote remains private even against future adversaries with quantum computers or unlimited computational power.

Here's the crucial insight: if your calculator is honest, it computes the correct tracker, and you find your vote. If it were corrupted and trying to deceive you, it faces an impossible task—it doesn't know what's on the tally board (it's been isolated), it doesn't know other voters' challenges (they're unique), and it cannot guess a valid tracker. The probability of successfully guessing is:

Pr[guess]=1/q which is negligibly small (approximately 1 in 1077 for typical parameters where q≈2256).

You observed the isolation. You provided the challenge. The calculator couldn't coordinate its story with the outside world. Therefore, you know the verification is genuine.

This is individual verifiability without trustees—not depending on the calculator being trustworthy, not depending on authorities being honest, not depending on cryptographic secrets staying secret. It depends only on the isolation you can observe and the discrete logarithm hardness assumption.

⚠️ Bulletin Board Presentation Assumptions

Trustee-free individual verifiability depends on voters' ability to retrieve their unique challenge. To bind the challenge to each voter's identity while preserving voters' anonymity, the challenge is derived as ei=Hash(seed∣Ii) where Ii=Comξi(Idi) is the voter's identity commitment. In practice, the voting device generates a link {{Bulletin_Board}}#{{xi}}&{{Id}} that voters forward to their chosen verification machine, which retrieves the seed and derives the challenge locally. The URL fragment parameters (after #) remain client-side, allowing the browser to display the identity string (e.g., passport number) for voters to verify commitment ownership—preventing tracking.

The critical vulnerability lies in man-in-the-middle attacks on bulletin board access. Multiple infrastructure layers enable such attacks: DNS hijacking redirects to malicious servers, compromised certificate authorities enable TLS interception, corrupt administrators present personalised false views, and compromised browsers, operating systems, or hardware intercept access directly. If a corrupt vendor colludes with any of these attack vectors, voters could be deceived into entering another voter's challenge, enabling a many-to-one attack where votes are cast silently in place of legitimate voters. (Making the seed 2× larger than individual challenges would prevent voters from entering the seed itself.)

While the risk of bulletin board deception also exists in other verifiable voting schemes, trapdoorless tracker construction forces adversaries to gamble. In Benaloh-style audits, attackers can adaptively modify unverified ballots. In Selene-type systems, possession of a trapdoor allows an adversary freely manipulate the ballots. By contrast, trapdoorless tracker construction forces the adversary to commit to fraud during the voting phase, gambling that they can later control challenge delivery to the targeted voters. This removes adaptivity and increases the likelihood that large-scale manipulation will produce inconsistent evidence across voters and channels, making community-level detection feasible even if individual deception remains possible.

What You Need to Trust (And What You Don't)

✓ Individual Verifiability - No Trust Required

Your voting calculator can be completely corrupted, and you'll still detect if your vote was manipulated. The isolation prevents corrupt calculators from showing you other voters' trackers, and any fake tracker will fail when you look it up on the tally board.

⚠ Receipt-Freeness - Limited Trust Required

Only if you need protection from coercion does the voting calculator need to be tamper-resistant. This prevents coercers from extracting your real tracker or detecting whether you've set up a fake one.

Individual verifiability creates a challenge: if you can verify your vote, couldn't a coercer force you to prove how you voted? This is where decoy state simulation comes into play.

Your voting calculator can wear two faces, like an actor switching masks. In its genuine mode, it computes your true tracker using the formula t=eθ+e2λ. In its decoy mode, it displays a pre-configured tracker for a specific challenge—simulating verification rather than computing it.

The defence strategy is simple: verify first, then configure the decoy if needed. After obtaining your genuine, unique challenge and verifying your vote, you can configure the calculator to display a fake tracker from the tally board (pointing to the coercer's preferred choice) when your challenge is entered again. If the coercer later demands verification, you hand them the calculator and let them enter the challenge themselves. The calculator displays the pre-configured tracker, appearing to prove you voted as they demanded.

Here's the asymmetry: you know whether you configured decoy mode, but the coercer cannot tell. They have no control over what information flowed into the calculator while it was in your possession. You've already verified your real vote, giving you both verification capability and plausible deniability.

To prevent coercers from breaking this deniability, the device is designed to compute only one genuine tracker. This constraint prevents the extraction of the secret values θ and λ from the calculator. Without access to these secrets, a coercer cannot independently verify whether a displayed tracker is genuine or a decoy, making the defence work.

Known Limitations

⚠️ Severing the calculator from the voter: If a coercer severs the calculator from the voter before the tally board is announced, then it can completely bypass the defence. This requires active time-bound intervention during voting.

⚠️ Temporary device access coercion: A coercer briefly gains physical access to the calculator during the voting phase and secretly decides whether to install a decoy tracker, enabling later detection. This requires active, time-bound intervention during voting.

⚠️ Accidental selection of a coercer-controlled tracker: A voter may mistakenly choose a tracker from the public tally board that is known to or controlled by a coercer, allowing the coercer to distinguish whether the voter is presenting a genuine or fake tracker. This can be mitigated by providing pre-tallied decoy trackers indistinguishable from real votes.

⚠️ Italian (pattern) attack: With complex ballots, unique vote patterns visible on the public tally board can be used to single out individual voters. This is inherent to systems that publish individual ballots and is mitigated by keeping ballots simple.

All these mechanisms connect through a public bulletin board—a transparent ledger containing every submitted vote with its corresponding tracker. Anyone can download this ledger, verify the cryptographic proofs, recount the votes, and confirm the announced tally. The pseudonym braiding proofs ensure that all votes came from eligible voters. The tracker assignments prove each voter received a unique, unpredictable challenge. The shuffle proofs guarantee that votes and trackers were correctly anonymised.

PeaceFounder solves bulletin board integrity by using history trees, giving each voter a lightweight consistency proof chain that shows their vote appears on the same bulletin board everyone else sees. If the authority attempts to show different voters different boards or selectively drops votes, the fraud becomes immediately detectable with irrefutable evidence.

The combination enables verifiable remote voting in practice. One authority runs the infrastructure, providing operational simplicity, while public cryptographic proofs ensure transparent accountability. Anyone can audit the tally remotely, and disputes can be resolved through cryptographic proof rather than trust. The approach scales from small organisational elections to national democratic processes and, because privacy relies on information-theoretic properties rather than computational assumptions, votes remain private even against future adversaries with quantum computers if they ever become cryptographically relevant.

Don't trust these claims—verify them!

- Janis Erdmanis, PeaceFounder : centralised E2E verifiable evoting via pseudonym braiding and history trees, 2024.

- Rolf Haenni, Oliver Spycher, Secure Internet Voting on Limited Devices with Anonymized DSA Public Keys, 2011.

- Rolf Haenni, UniVote Protocol Specification, 2013.

- Roger Dingledine, Nick Mathewson, Paul Syverson, Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router, 2004.

- Scott A. Crosby, Dan S. Wallach, Efficient Data Structures for Tamper-Evident Logging, 2009.

- Janis Erdmanis, ShuffleProofs.jl : Verificatum compatible verifier and prover for NIZK proofs of shuffle., 2022.

- Douglas Wikstrom, A Sender Verifiable Mix-Net and a New Proof of a Shuffle, 2005.

- Douglas Wikstrom, How To Implement A Stand-alone Verifier for the Verificatum Mix-Net, 2011.

- Rolf Haenni, Philipp Locher, Reto Koenig, Eric Dubuis, Pseudo-Code Algorithms for Verifiable Re-encryption Mix-Nets, 2017.

- Janis Erdmanis, Unconditional Individual Verifiability with Receipt Freeness via Post-Cast Isolation, 2025.

- Peter Y. A. Ryan, Crypto Santa, 2016.

- Peter Y. A. Ryan, Peter B. Rønne, Vincenzo Iovino, Selene: Voting with Transparent Verifiability and Coercion-Mitigation, 2016.

- Ewa Syta, Philipp Jovanovic, Eleftherios Kokoris Kogias, Nicolas Gailly, Linus Gasser, Ismail Khoffi, Michael J. Fischer, Bryan Ford, Scalable Bias-Resistant Distributed Randomness, 2017-05.